Key Highlights

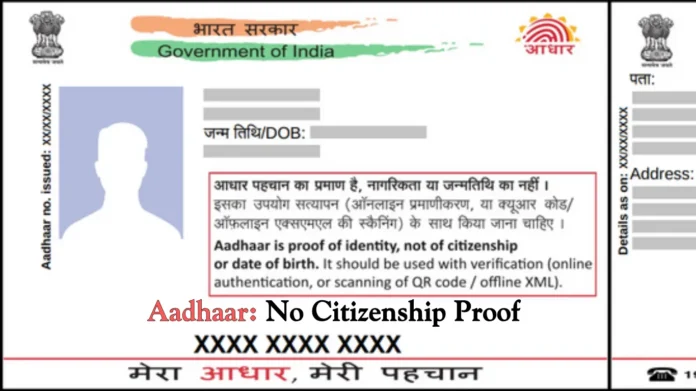

- Supreme Court affirms Aadhaar is proof of identity, not citizenship, and cannot grant voting rights automatically.

- Election Commission’s Special Intensive Revision (SIR) seeks accurate electoral rolls without relying solely on Aadhaar Citizenship Proof verification.

- Ongoing Supreme Court hearings focus on protecting voters’ rights and ensuring fair deletion processes in electoral rolls during SIR.

Opening Overview

Aadhaar citizenship proof stands at the center of a significant legal discourse in India. The Supreme Court has reiterated that Aadhaar cards do not qualify as proof of citizenship, clarifying its limited role as an identity document for social welfare benefits. As India undertakes electoral roll revisions under the Election Commission’s Special Intensive Revision (SIR), the question of whether Aadhaar holders can be automatically included as voters arises with urgency. Aadhaar Citizenship Proof With millions of names being verified or deleted, the court underscores that citizenship validation must adhere to constitutional safeguards rather than procedural convenience. This ruling aligns with the Aadhaar Act’s vision where Aadhaar serves resident identification, not conferring voting rights or citizenship status.

Legal Status of Aadhaar Citizenship Proof Verification

- Aadhaar is mandated by law as a welfare identification tool and cannot legally confer citizenship or domicile status in India.

- The Supreme Court confirms Aadhaar’s role is limited to identity and residence verification; citizenship must be established through recognized documents under the Citizenship Act of 1955.

- The Election Commission uses Aadhaar as one of many documents for voter list inclusion; it is not conclusive proof to confer electoral rights.

- UIDAI explicitly states Aadhaar is not a citizenship document, emphasizing the need to separate identity authentication from citizenship determination.

Aadhaar citizenship proof remains a contentious issue in India’s legal framework. Created under the Aadhaar Act of 2016, the document primarily facilitates targeted delivery of government subsidies and services to residents. Courts have consistently ruled that possession of an Aadhaar card does not imply Indian nationality. Section 9 of the Aadhaar Act explicitly declares it proves neither citizenship nor domicile. This position prevents misuse where non-citizens, such as long-term residents from neighboring countries, might seek electoral benefits solely based on Aadhaar possession.

The Supreme Court bench, led by Chief Justice Surya Kant, reinforced this during recent hearings on electoral roll revisions. Justices emphasized Aadhaar’s statutory purpose limits it to identity checks, not nationality confirmation. Legal precedents, including judgments on voter inclusion forms, uphold that citizenship demands stricter evidence like birth certificates or passports. This clarity protects the electoral process from potential infiltration while allowing Aadhaar’s practical utility in verification.

The Aadhaar card is not proof of citizenship or domicile says the @GoI_MeitY in this answer to my question in Parliament on the definition of Aadhar. Why was this not made clear in the last decade when every government agency-including @ECISVEEP was constantly demanding Aadhar?… pic.twitter.com/EISEYOsLap

— Sagarika Ghose (@sagarikaghose) August 2, 2025

Role of Special Intensive Revision (SIR) in Electoral Roll Accuracy

- SIR is a constitutionally mandated exercise aimed at cleaning electoral rolls by verifying existing voters and removing duplicates, deceased voters, or non-citizens.

- The revision process is comprehensive, involving house-to-house verification and submission of relevant documents including Aadhaar as an identity proof among others.

- The Election Commission holds jurisdiction to approve or reject voter inclusion applications (Form 6), ensuring only legitimate citizens remain on rolls.

- The Supreme Court is examining challenges to SIR in Tamil Nadu, Kerala, and West Bengal focusing on procedural fairness and voter rights protection.

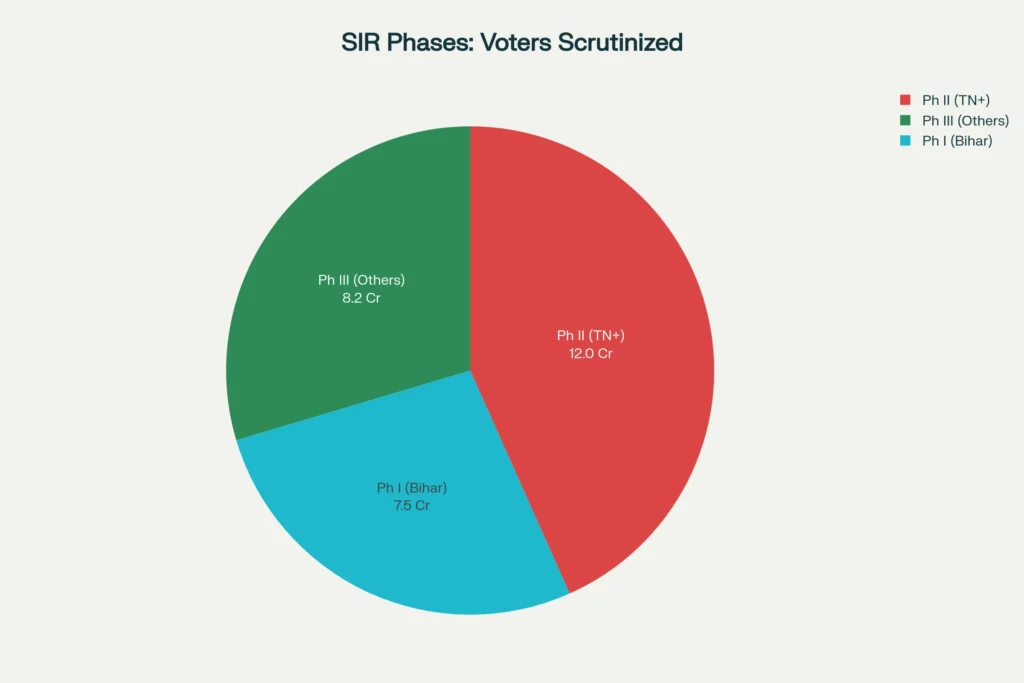

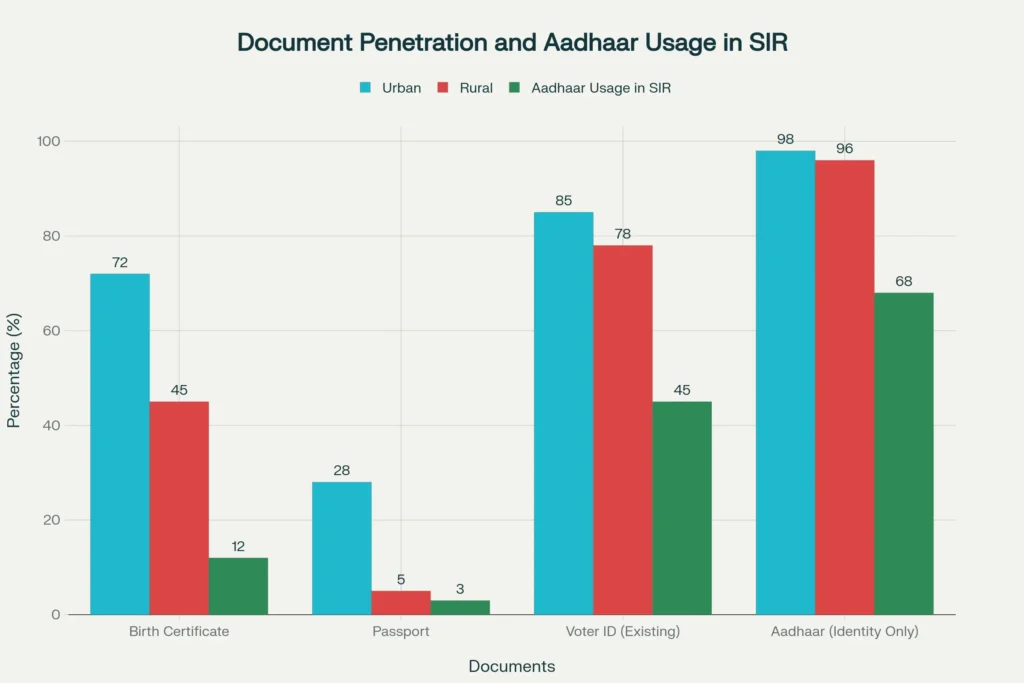

Special Intensive Revision (SIR) represents the Election Commission’s proactive step to maintain electoral roll integrity ahead of key state polls. Launched in phases across Bihar, Tamil Nadu, Kerala, and West Bengal, SIR mandates fresh enumeration through booth-level agents conducting door-to-door checks. Voters submit Form 6 applications with supporting documents, where Aadhaar serves as one option among 12 approved identity proofs, but never as standalone Aadhaar citizenship proof.

The process targets anomalies like duplicate entries, shifted residents, and deceased names, which official data shows affect up to 5-7% of rolls in revision states. Election Commission directives, updated post-court orders, instruct officials to authenticate all documents rigorously. For instance, in Bihar’s SIR phase, over 7 crore voters underwent scrutiny, resulting in millions of corrections. This exercise aligns with Section 23 of the Representation of the People Act, 1950, empowering the Commission to curate accurate lists without compromising eligible citizens’ rights.

Constitutional Safeguards and Voter Rights Amid Aadhaar Use

- The Supreme Court stresses that any deletion from voter lists must follow a reasonable, fair process with due notice to affected individuals to protect democratic participation.

- The burden of filing forms or proving identity should not unfairly exclude illiterate or vulnerable voters, highlighting constitutional safeguards above procedural technicalities.

- Aadhaar’s legal status as identity but not citizenship means Aadhaar holders cannot be automatically enfranchised without additional citizenship proof.

- Ongoing petitions urge the court to balance electoral integrity with the right to vote, scrutinizing the Election Commission’s document verification authority and deletion criteria.

Constitutional principles under Articles 14, 19, and 326 guarantee every citizen’s voting right, prompting Supreme Court scrutiny of SIR’s implementation. The bench questioned whether non-citizens with Aadhaar could claim voter status, underscoring that Aadhaar citizenship proof falls short of electoral eligibility. Petitions by figures like Kapil Sibal highlight risks to illiterate voters facing form-filling hurdles, arguing presumptive validity of existing rolls unless disproven.

Courts mandate prior notice and hearing opportunities before deletions, ensuring fairness. The Election Commission, described not as a “post office” but an active verifier, assesses Form 6 submissions holistically. This balances integrity against exclusion, with directives allowing online claims and extended deadlines for vulnerable groups. Recent hearings fixed response timelines, with rejoinders due soon, signaling deeper judicial oversight on Aadhaar’s electoral boundaries.

Challenges and Implications for Future Electoral Reforms

- Petitions challenge SIR’s burden on ordinary voters, particularly in literacy-challenged regions, demanding streamlined processes.

- Supreme Court interventions clarify Aadhaar’s limits, pushing Election Commission toward multi-document verification frameworks.

- Broader implications include nationwide roll purification, reducing bogus voting while safeguarding genuine citizens’ enfranchisement.

- Legal debates highlight tensions between technology-driven efficiency and constitutional equity in India’s democracy.

Challenges to SIR reveal systemic tensions in linking digital identity like Aadhaar Citizenship Proof processes. Critics argue mandatory document submission disproportionately impacts rural and migrant populations, where Aadhaar penetration exceeds 95% per UIDAI data, yet birth records lag. Supreme Court observations stress procedural reasonableness, rejecting blanket reliance on Aadhaar Citizenship Proof

Future reforms may expand acceptable documents or integrate passport-linked databases for seamless verification. States like West Bengal report over 2 crore claims processed, with 15% deletions contested. This episode prompts Election Commission guidelines emphasizing hybrid proofs, ensuring technology aids rather than hinders democracy. Nationwide rollout could standardize practices, minimizing litigation while fortifying polls.

Final Perspective

The Supreme Court’s firm reiteration that Aadhaar is not proof of citizenship reinforces the principle that electoral rights in India are constitutionally safeguarded and cannot be dispensed based on a welfare identification document alone. The ongoing Special Intensive Revision (SIR) fulfills a critical role in electoral roll accuracy but must respect voter rights and fairness, ensuring citizens are neither unjustly excluded nor non-citizens enfranchised. As petitions and hearings progress, this legal stance upholds democratic integrity by separating Aadhaar’s welfare function from the fundamental right to vote, emphasizing that citizenship verification requires more rigorous legal standards.