Summary

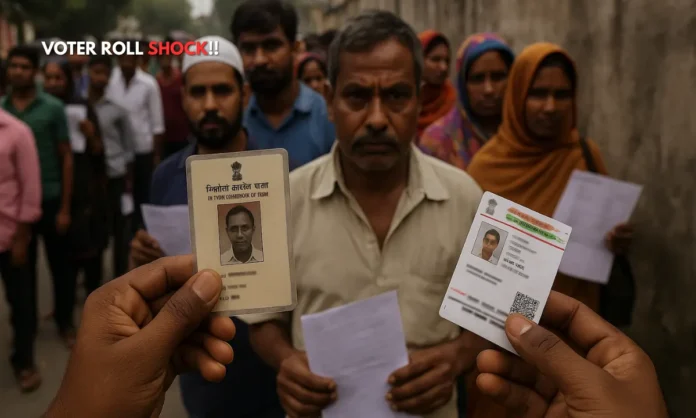

- The Election Commission of India (ECI) launched a Special Intensive Revision (SIR) of Bihar’s electoral rolls with a tight timeline and stringent new document requirements.

- Voters not listed in the 2003 electoral roll must now furnish documents for themselves and their parents, sparking fears of mass disenfranchisement.

- Critics say the process may bypass legal safeguards and resemble the controversial NRC framework, especially amid Bihar’s challenges of low literacy, migration, and digital access.

Urgency in the Shadows: Bihar’s Unprecedented Electoral Revision Explained

With Assembly elections due by November 2025, the Election Commission of India has announced a sweeping Special Intensive Revision (SIR) of electoral rolls in Bihar. On paper, this exercise is meant to address standard issues like urbanisation, migration, and deceased voters. But the timing, scale, and procedural shift have triggered deep concern across legal, political, and civil society quarters. Critics argue this revision is less about routine voter roll maintenance and more about implementing a de facto citizenship verification regime.

Unlike previous revisions, the current SIR makes the 2003 electoral roll a baseline for citizenship presumption. Those not listed on it—i.e., any voter added in the last 21 years—must now submit documentary proof of eligibility, not only for themselves but also for their parents. With high rates of out-migration, low literacy, and limited access to digital infrastructure, the move threatens to disenfranchise thousands, particularly from Bihar’s most vulnerable communities.

This investigation explores the political motives, operational hurdles, and legal risks underpinning this hurried revision. Is this about cleaning up voter rolls, or is it an NRC-like process in disguise?

ECI launches Special Intensive Revision (SIR) of electoral rolls in India, s/w Bihar. In a first, EC cites "inclusion of foreign illegal immigrants" in electoral rolls a reason for SIR. In Bihar, last SIR in 2003, cut off yr as citizenship proof. Link–>https://t.co/WCZG8sy2Ia pic.twitter.com/aFLxm1kBdo

— Abhishek Angad (@abhishekangad) June 25, 2025

Legal Justification or Legal Gymnastics?

- The ECI invoked Section 21(3) of the Representation of the People Act, 1950, and Rule 25 of the Registration of Electors Rules, 1960.

- The last such intensive revision in Bihar took place in 2003; nothing similar has been attempted since.

- The June 24, 2025 order redefines the 2003 roll as a benchmark for citizenship presumption.

- Those not listed in 2003 must now produce separate documents for themselves, their father, and mother.

- This process appears to bypass Rule 21A, which mandates due process before deletion from the rolls.

At the heart of the legal unease lies the reinterpretation of voter eligibility. Paragraphs 11 and 12 of the ECI order effectively devalue all electoral registrations post-2003 unless backed by multiple official documents. In simple terms: if you’re not on the 2003 list, your voter status and even your citizenship are now in question until proven otherwise.

This has raised foundational questions. What happens to votes cast by these individuals in the past 21 years? Are election outcomes since 2003 invalid? And most importantly, is it legally permissible to overwrite Form 6-based voter registration with an unlegislated demand for parentage documentation? Legal scholars argue this opens the ECI to potential constitutional litigation, especially for violating the right to be heard before voter deletion.

Disenfranchisement by Design? The Practical Realities on the Ground

- The schedule began June 25, 2025—just a day after the order was issued.

- BLOs are tasked with house-to-house visits for both distribution and collection of forms.

- Draft rolls are due by August 1; final publication by September 30.

- Forms are currently only available online; electricity and digital literacy gaps persist in rural Bihar.

- Millions of Bihari workers are interstate migrants unlikely to be home during the survey.

The ECI’s compressed three-month schedule raises serious doubts about operational feasibility. In a state where electricity is unreliable, digital literacy is low, and millions work in other states, expecting rapid compliance with such document-heavy, form-intensive procedures borders on fantasy. BLOs are expected to distribute pre-filled forms, collect updated versions, and verify citizenship evidence—twice—within weeks.

The risk is clear: this could end up being a selective revision, with only the most privileged or urban voters completing the process. The ones left out? Likely the poor, the mobile, and the illiterate—those least capable of navigating this bureaucratic gauntlet. Critics argue that disenfranchisement isn’t a side effect; it’s structurally baked in.

The Citizenship Question No One Is Asking Aloud

- Critics liken the revision process to a stealth NRC roll-out in Bihar.

- The requirement for parent documents echoes CAA-NRC protest fears.

- The phrase “illegal immigrants” in ECI’s justification raises red flags.

- Transparency promises are undercut by exclusive data access for officials.

- Political context, including voter base realignment, cannot be ignored.

For many observers, this exercise has echoes of the controversial NRC and CAA debates that roiled India in 2019-20. The requirement to furnish parental documentation, combined with opaque data verification and references to illegal immigrants, sets off alarm bells. While the ECI claims transparency, it also restricts access to uploaded documents to “authorised personnel only.”

In a state like Bihar, where caste and community dynamics deeply influence voting patterns, such a revision may carry political undercurrents. Many fear this could become a tool to suppress certain demographics, particularly Muslims and EBCs, ahead of a contentious election.

Ballot or Barrier?

The ECI’s Special Intensive Revision of electoral rolls in Bihar is being pitched as a clean-up act. But its implications are anything but procedural. With unrealistic timelines, opaque legal shifts, and document-heavy demands that mimic the NRC model, this exercise risks disenfranchising the very people it’s meant to empower.

Whether intentional or not, the SIR has become a flashpoint in India’s ongoing debate over citizenship, voting rights, and democratic access. And with elections looming, the price of bureaucratic overreach may be paid in the currency of lost votes—and lost faith.